It recently was reported that Joe Scarborough and Mika Brzezinski have been broadcasting their “Morning Joe” news show from their new home in Jupiter, Fla. with backdrops of Washington, D.C.1 Before the move to Florida, a state with no income or estate taxes, Scarborough and Brzezinski lived in Connecticut, a relatively high income and estate tax jurisdiction. As taxpayers receive their 2018 tax bills, it’s anticipated that there will be large migrations to low tax domiciles in an attempt to reduce 2019 taxes.

Tax savings certainly is an attractive reason for a client to exchange his high tax domicile for a low one, but it’s not quite as easy as simply moving to a new house or spending 183 or more days in a low tax jurisdiction. Severing domicile requires affirmative actions to demonstrate the client’s desire to leave and establish a new domicile elsewhere.

“Domicile” refers to the place where an individual maintains her permanent home and the place to which the individual intends to return whenever absent. For most states, two essential elements of domicile are: (1) an actual residence, and (2) an intent to remain indefinitely. While an individual can be a “resident” of more than one location, an individual can only have one domicile. Moving to a new location doesn’t effect a change in domicile unless the individual manifests an intention to make the new residence her domicile. Once a domicile is established, the domicile continues until the individual moves to a new location with the bona fide intention of making her permanent home in such new location.

High Tax Jurisdictions

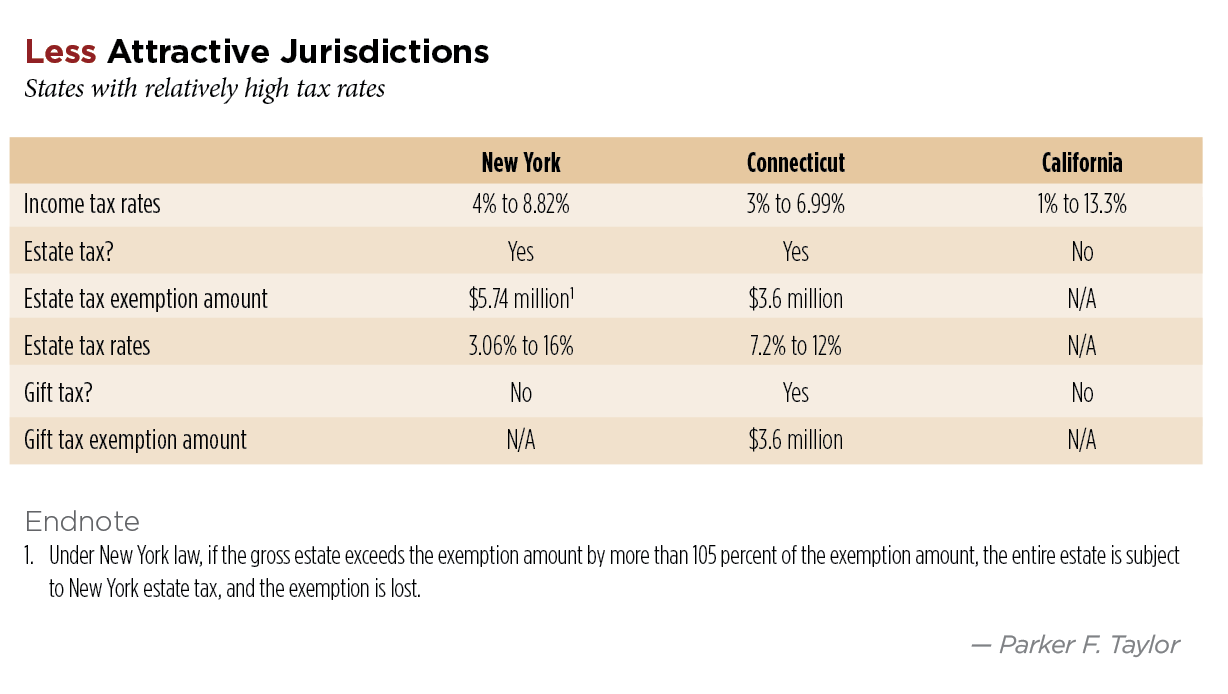

California, Connecticut and New York are states with relatively high state income tax rates and New York and Connecticut additionally impose state estate taxes—and a gift tax in Connecticut—which makes these jurisdictions less attractive to high-net-worth individuals looking to reduce their tax bills. This only has been compounded by the 2018 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s (TCJA) virtual elimination of the state and local income tax deduction. In fact, it was recently reported that New York Governor Andrew Cuomo cited the TCJA as a major reason why many New Yorkers are changing their domiciles to Florida.2 “Less Attractive Jurisdictions,” p. 22, summarizes the current tax rates and exemption amounts for these high tax states.

The criteria for tax domicile for these states are quite similar. In general, a resident for income tax purposes is any individual domiciled in the state or any individual who’s domiciled elsewhere but “maintains a permanent place of abode” in the state and is in the state for an aggregate of more than 183 days of the taxable year.3 State tax authorities will consider a number of factors in determining whether an individual is domiciled in the state. No one particular fact is conclusive; the conclusion as to whether a domicile has been changed depends on an appraisal of the facts and circumstances of each particular case.4

A crucial factor in a change of domicile to any state will be the individual’s intent to make that new state her permanent home.5 For example, a New York appellate court recently held that a taxpayer failed to abandon his New York domicile by merely spending in excess of 183 days in Florida.6 In that case, the taxpayer historically had filed resident income tax returns in New York until 2006 when he filed a nonresident income tax return in New York claiming that he’d abandoned his New York domicile and was now a Florida domiciliary because he spent more than

183 days at his Florida condominium, which he’d owned since the 1980s.7 The court noted that the taxpayer continued to receive mail, see doctors and conduct business in New York.8 He also retained and occasionally used a residence in New York where his wife resided and that was within close proximity to his daughter and grandchild.9 The court concluded on this basis that there was substantial evidence supporting the determination that the taxpayer hadn’t abandoned New York as his domicile.10

Low Tax Jurisdictions

Florida, Nevada and Texas have no state income, estate, or gift tax, which makes them appealing tax domiciles for individuals currently in high tax jurisdictions.

If your client wants to be considered a domiciliary of a particular state, he’ll need to take as many of the following steps as practicable to demonstrate his intent to make his permanent home in that state and abandon his prior domicile. After all, it takes more than merely spending 183 days in a low tax jurisdiction to change domicile.

(a) Register to vote in his new state and vote there in all upcoming elections (including local elections). If he makes local political contributions, make them in his new state rather than in the state of his former residence.

(b) Transfer his driver’s license, automobile registrations and boat registrations to his new state.

(c) Declare his new state as his mailing address and residence address on all federal tax returns. Report and pay taxes imposed on residents in his new state, and cease to report and pay taxes imposed on residents in his former state.

(d) Spend as much time as possible in his new state and spend as little time as possible in his former state. His travel records, telephone and utility usage should reflect this.

(e) Declare his new state as his place of domicile and residence on all forms or documents that require a listing of residence (for example, bills, contracts, deeds and leases).

(f) Declare his new state as his principal address for sending and receiving correspondence. Have newspaper and magazine subscriptions sent to the new address.

(g) If available in his new state (such as Florida or Nevada), declare himself as a resident by filing a sworn statement in the office of the clerk of the circuit court for his county of residence.

(h) Execute new estate-planning documents that recite his new state as his domicile.

(i) Terminate active participation in businesses or partnerships that are located in his former state and investment in or management of closely held corporations in his former state, to the extent he can. Terminate professional licenses in his former state, and establish new professional licenses in his new state.

(j) Terminate social and religious organization memberships in his former state (or, transfer to nonresident membership, if available). Establish similar ties in his new state.

(k) If he maintains a safe deposit box, maintain it in his new state, and keep family records and valuables there.

(l) Close out bank accounts in his former state, if any, and establish new accounts in his new state.

(m) Move most or all of his personal possessions to his residence, including items of significant sentimental value to him.

(n) Register any school-age children in schools in his new state. Terminate pet licenses in his former state, and license his pets in his new state.

(o) Ensure that his pattern of employment is based primarily in his new state. If he receives unemployment compensation benefits, make sure he receives them in his new state.

(p) Sell real property located in other states, and purchase real property in his new state.

(q) Relinquish burial plots in other states, and purchase new ones in his new state.

Additional Steps Needed

In the current tax regime, your client can realize significant tax savings by changing his domicile to a low tax jurisdiction. However, it takes more than merely moving to a state to effectively change domicile for state income and estate purposes. By not taking the additional steps to indicate his intent to make his new state his permanent home and abandon his old domicile, he may be subject to unintentional state income and estate taxes and other costs associated with a state tax audit. Clients should take care to avoid conflicting domicile circumstances when planning for a domicile change.

Endnotes

1. https://pagesix.com/2019/01/26/the-tax-strategy-behind-joe-and-mikas-florida-studio/.

2. www.wsj.com/articles/out-of-state-buyers-flock-to-miami-11549325267.

3. N.Y. Tax Law Section 605(b); Conn. Gen. Statutes 12-701(a)(1).

4. 20 NYCRR 105.20(d)(2); Conn. Reg. Section 12-701(a)(1)-1(d); www.ftb.ca.gov/aboutFTB/manuals/audit/rstm/2000.pdf.

5. Conn. Reg. Section 12-701(a)(1)-1(d); 18 CCR Sec. 17014(c).

6. Matter of Campaniello v. New York State Div. of Tax Appeals Trib., 2018 NY Slip. Op. 03400 (2018).

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.