To gift or not to gift, that is the question.1 To not gift means keeping the asset or doing something to cause it to be included in an estate for estate tax purposes. Gifting means the opposite: a lifetime transfer that causes future asset appreciation to escape estate tax. While less complex than the famed question posed by Prince Hamlet, families that hold appreciated assets and are (or may be) exposed to estate tax often wrestle with the choice.

Why the dilemma? Because the sting of death brings with it one tax blessing: an income tax cost basis step-up to market value on all assets included in an estate.2 This makes it appealing for clients to tempt estate tax fate and hold on to low income tax basis assets. The risk, of course, is fate not being on your client’s side: Estate tax ends up far higher than planned (for example, due to a change in the tax laws).

Why Worry Now?

For several reasons. First, the 2018 tax law doubled the federal estate tax exemption from $5.6 million to $11.2 million per individual ($22.4 million exemption for a married couple) for decedents passing before 2026. For 2019, the exemption increased to $11.4 million but will return to pre-2018 exemption levels ($5.6 million per person, adjusted for inflation) in 2026 unless Congress acts to extend the new exemption amounts. Second, if a Democratic President and Democratic Senate come to pass in 2020, gift and estate tax exemptions could be reduced before 2026.3 While changes in the tax law would likely be prospective, planning to avoid any enactment date rush may be time well spent.

Inputs or Variables to Consider

“It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.”

—John Maynard Keynes

The trade-off is between saving income tax and sheltering future asset appreciation from estate tax. These rules of thumb seem more right than wrong:

1. The lower the basis-to-market ratio, the higher the income tax basis step-up opportunity.

2. The more an asset value exceeds federal and, if relevant, state estate tax exemptions, the more appealing a gift becomes.

3. The time horizon (or measurement period) matters. When the asset basis-to-market ratio is low, the post-gift annual rate of return required for a gift to beat keeping the asset can be very high, especially when measured over short periods of time.

4. The longer an asset is held after it passes through an estate, the more appealing a gift can become.

5. When a state has its own high estate tax rate, a gift often beats keeping the asset, especially when the basis-to-market ratio is high.

6. When families face estate tax, the arithmetic favors paying gift taxes over estate taxes.4

7. A higher federal long-term capital gains rate increases the value of an income tax basis step-up, especially when the estate tax rate doesn’t change.

Caveats

Several caveats are important. First, as mentioned by authors David A. Handler and Patricia Ring,5 our post-gift annual rate of investment return includes only appreciation, not income. Second, the return is an after-tax number. Third, we ignore valuation discounts.6 Fourth, we assume the gift asset is sold in the same year the asset is included in the estate. This, we know, may not be true; assets received by gift or inheritance are often held for many years before income tax is paid. Lastly, as mentioned above (point 7), we assume no change in the long-term capital gains rate, which often impacts the gift-keep arithmetic.

Five Scenarios

Scenario 1: Gift and estate tax exemptions sunset back to $5.6 million in 2026/no state tax. Sarah, single, and a resident of Wyoming (no state tax), holds $11.4 million worth of low basis securities. She holds enough other assets exposing her to estate tax. She asks if it makes most sense to gift her low basis securities to her family now or pass them along to her family through her estate. Keeping the asset appears to be the better choice, especially when the basis-to-market ratio is low and if Sarah is in poor health. (See “Scenario 1 Figures,” this page.)

For example, if the basis-to-market ratio is zero, the annual post-gift appreciation rate must be 24.11% over five years for the estate tax saving on post-gift appreciation to exceed the income tax saving that comes from keeping the low basis securities in her estate. Naturally, the required annual return number declines as the time period extends and the basis-to-market ratio increases. If the estate tax exemption sunsets back to $5.6 million (indexed for inflation), the rate of return for a gift to beat keeping the asset falls dramatically in the Year 10 numbers (which includes 2026, Year 7). As the estate tax exemption falls, saving estate tax rises in value even if the post-annual gift appreciation rate is modest. In this scenario and all scenarios that follow, a 0% hurdle rate is exactly what it implies: the return for a gift to beat keeping the asset is zero. In reality, and as authors Handler and Ring pointed out, a negative return of some amount may often be the true gift-beats-keep hurdle. For discussion purposes, we limit our hurdle rate to zero.

Scenario 2: Gift and estate tax exemptions sunset back to $5.6 million in 2026/high state tax. Now assume Sarah is a resident of Minnesota (9% state income tax rate and 16% estate tax rate over $2.7 million). Minnesota, from now on, is our “high tax state.” Here, because of the 16% state estate tax rate, the post-gift annual rate of return for a gift to beat keeping the asset in all years declines. (See “Scenario 2 Figures,” p. 30.)

Scenario 3:Gift and estate tax exemptions remain same/no state tax. Now consider the same facts as in Scenario 1, but assume the federal estate tax exemption remains the same. Without the steep loss in federal estate tax exemption set to occur in Year 7 (2026), keeping the asset in the estate gains in appeal, especially when the basis-to-market ratio is low. (See “Scenario 3 Figures,” p. 30.)

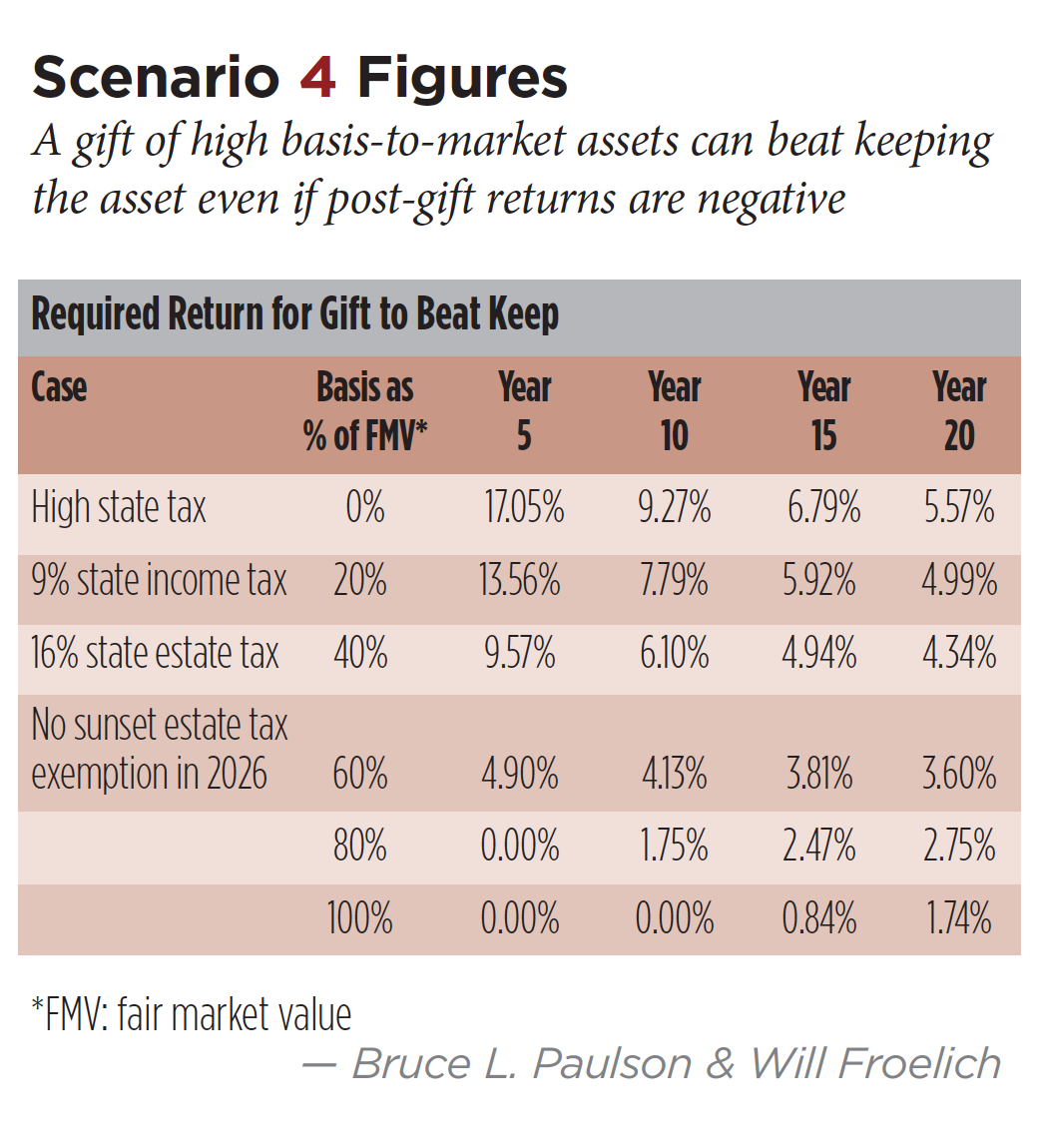

Scenario 4: Gift and estate tax exemptions remain same/high tax state. Following the same path, consider the same facts as in Scenario 2, when the federal estate tax exemption remains the same, and Sarah is a resident of Minnesota. When the basis-to-market ratio is high and a high state estate tax is looming, a gift of high basis-to-market assets can beat keeping the asset even if post-gift returns are negative. (See “Scenario 4 Figures,” p. 31.)

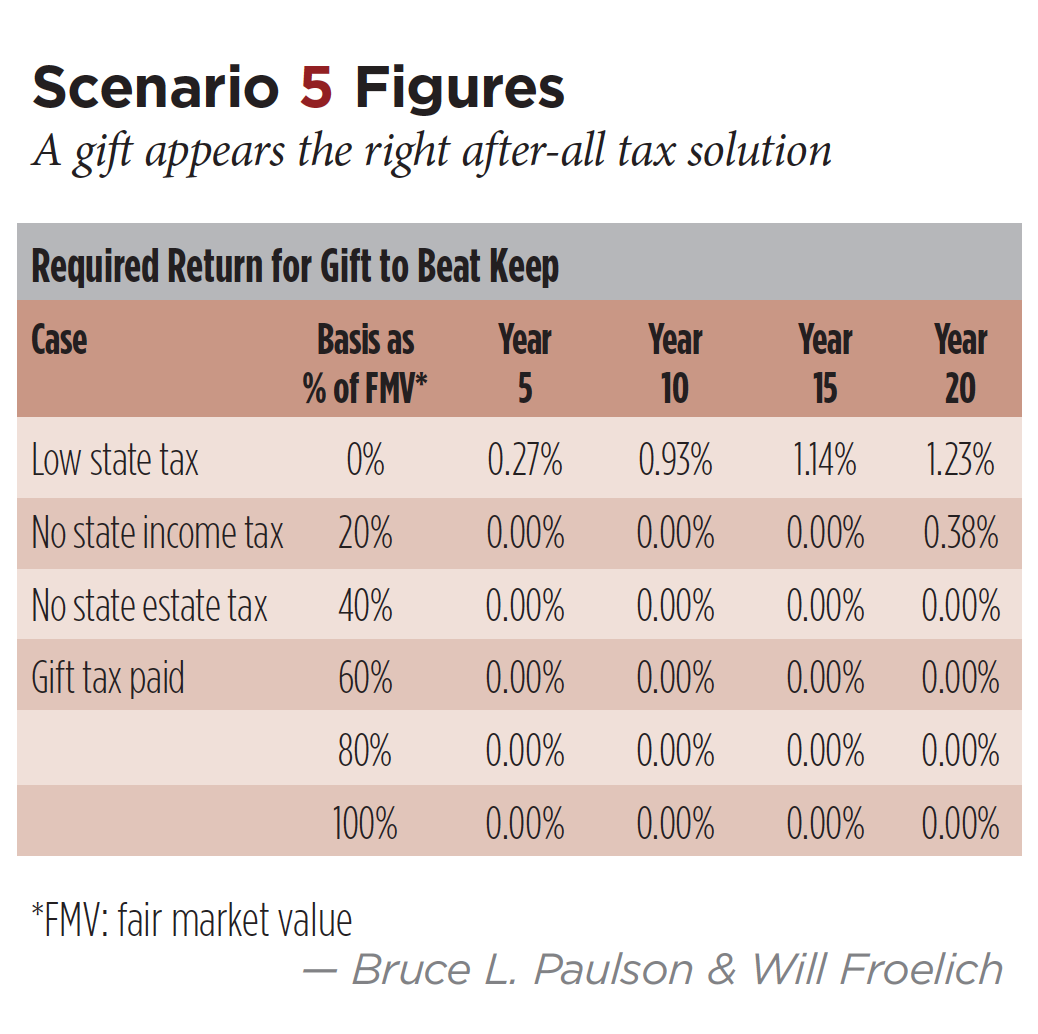

Scenario 5: Gift tax paid and no state tax.Now consider the facts in Scenario 1, but Sarah, exposed to estate tax, has no remaining gift and estate tax exemption. She asks if she should pay gift tax to make a lifetime transfer or pass the same asset through her estate. Gift taxes paid increase income tax basis of the gifted asset, the amount limited by the basis-to-market ratio of the asset at the time of transfer,7 a calculation we account for in our numbers. Keep in mind if she doesn’t pay gift taxes, these gift tax dollars remain in her estate and are later exposed to both federal and state estate tax (if applicable). We assume gift tax dollars not paid grow annually at 5%. (See “Scenario 5 Figures,” p. 31.)

The numbers here shouldn’t surprise. The estate tax system is tax inclusive, meaning funds that are used to pay the estate tax are themselves subject to the tax. That is, the estate tax is imposed on the entire value of the estate, including the assets that will ultimately pass to the federal government. In contrast, the gift tax is calculated only on the value of property transferred. This means the amount paid by the transferor (for example, the gift tax) isn’t subject to tax. Hence, the gift tax is said to be tax exclusive. Moreover, as mentioned above and included in our calculations, gift tax dollars paid increase the income tax basis, which reduces the capital gains tax when gifting the asset is compared to keeping it. Because the estate tax rate is higher than the long-term capital gains rate, and the effective long-term capital gains rate is reduced (marginally) by the basis adjustment for gift tax dollars paid, a gift appears the right after-all tax solution for Sarah (except if she dies within three years of the transfer, under which IRC Section 2035 brings back into the estate tax calculation gift tax dollars paid).

Planning Considerations

“Simple it’s not, I’m afraid you will find, for a mind maker-upper to make up his mind.”

—Dr. Seuss, Oh, The Places You’ll Go!

Several planning considerations come to mind to discuss with your clients:

Gift selection. The income tax basis step-up is more important for some assets than others. If a lifetime gift asset when sold will be taxed as ordinary income8 or a rate higher than long-term capital gains, the basis step-up gains in appeal.

Valuation. No one has a crystal ball. When an appreciated asset seems fully valued and likely to be sold, gifting to heirs to bear a large income tax burden makes little sense.

Payment of gift taxes. When gift taxes are paid, the best gift asset (taxwise) is one whose basis-to-market ratio at the time of the gift allows full or maximum use of the step-up in income tax basis for gift taxes paid.

Valuation discounts. Look carefully at whether claiming a valuation discount on a gift comes at too high an income tax cost. In some cases, higher valuation may be the better income tax answer (to receive full basis-step up in an estate or a higher income tax basis adjustment for gift taxes paid).

Upstream gifts. Consider making gifts to parents who don’t have enough wealth to make full use of their estate tax exemptions.9 The gift could be outright or in a trust that includes a power that causes the trust assets to be included in the parent’s estate. The asset, then, could return to the original owner or his heirs with a new, now higher, income tax basis.

Obtain a basis step-up for existing trust assets. Families with low basis assets in existing trusts might see whether old trusts, without causing tax harm, can be modified or decanted to include testamentary powers of appointment that cause the assets to be included in the power holder’s estate, stepping up the income tax basis of the asset subject to the power.10

Grantor retained annuity trusts (GRATs). When the gift being considered has a low basis-to-market relationship and is volatile in price, short-term GRATs remain attractive. Likewise, with record low interest rates, innovative attorneys are writing about funding very long-term (for example, 99-year) GRATs, a concept that centers on including assets in an estate (hence, receiving some income tax basis), but betting on the chance that interest rates in the future will be higher than they are today. When a grantor doesn’t outlive the stated GRAT term, the amount of property required to be included in his estate is only the amount of property needed to produce the state (fixed) annuity payment over the remaining term of the trust.11

Grantor trusts. When low basis assets are the best or only asset to gift, look at making the gift to a grantor trust. The grantor can retain a power to reacquire trust assets12 (with low tax basis) in exchange for high basis assets (cash, even if raised by borrowing). This way, the post-gift appreciation escapes estate tax, but the low income tax basis asset is brought back into the estate to benefit from the income tax basis step-up.

Life insurance. When tradeoffs between paying income taxes or estate taxes exist, consider using term insurance to reimburse, in part or whole, for the risk of making the wrong choice regarding gift or keep. What this looks like will depend on the facts and objectives of the family.

Hedging. When the low basis asset is a concentrated, marketable security and the numbers favor keeping the asset in the estate, consider hedging the downside price risk, especially when the years to estate tax inclusion are few.

Use of debt. A loan might be taken out against a low basis asset to create an enforceable claim that reduces the borrower’s taxable estate.13 The low basis asset remains in the gross estate and eligible for full step-up in basis. The cash, or loan proceeds, might be used to gift, exercise a power of appointment or fund a new estate-planning transaction.

Exchanged fund. When the tax arithmetic favors keeping the asset but doing so exposes the investor to excess single security (or industry) risk, consider an exchange fund. Exchange funds allow partners to contribute low cost basis securities into a fund and receive back, without triggering tax, a pro rata share of diversified stocks in a variety of industries.14 If capturing the income tax basis step-up is a major reason not to reduce the higher risk (or volatility) that comes with owning one or several stocks, investors who are willing to part with future upside return from all or part of the position may find holding an exchange fund (and carrying “it” into an estate) is a better choice than doing the same with one or several securities. If an investor dies while invested in the fund, the estate or beneficiary of the deceased receives the fund interest with a stepped-up income tax basis. If the estate or beneficiary later redeems its exchange fund interest, it receives back in-kind a basket of securities with basis equal to the stepped-up amount, plus any normal partnership adjustments to the capital account that have occurred since the date of the investors passing.

Separate account equity index (SAEI).15 While not alone an answer or variable into the gift-keep equation, families that hold large, low basis concentrations in one of several securities may be wise to dial down their single stock risk exposure by investing other dollars in a separate account equity index product. Unlike mutual funds or exchange traded funds, investors in SAEI receive tax basis in every security in the account and can assiduously harvest tax losses that can be used over time to offset capital gains on the sale of the low basis, concentrated security. About $2 of SAEI exposure is required (over seven to 10 years) to offset $1 of unrealized long-term capital gains. The SAEI portfolio could be long or hedged (using options).

Testamentary charitable lead trust (CLT). When the arithmetic favors saving income tax by keeping an asset in an estate and charitable desires are present, consider reducing the estate tax cost by funding a testamentary CLT.

Non-Tax Inputs

“There is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.”

—H. L. Mencken, American Journalist

How true—and an appropriate ending to our discussion. The arithmetic is just one piece of the puzzle. While the numbers are important, a family’s broader wealth transfer goals and objectives should precede all else. Lifetime spending needs, future market assumptions, projected lifetimes and preparedness of the next generation are just a few of the many non-tax inputs into the gift or keep equation.

Endnotes

1. This article follows an earlier excellent article, written by David A. Handler and Patricia Ring, “Lifetime Transfer of Appreciating Assets,” Trusts & Estates (December 2016).

2. Under Internal Revenue Code Section 1015(a), the basis of property acquired by gift is the same as it would be in the hands of the donor. If the basis is greater than the property’s fair market value (FMV) at the time of the gift, the basis is generally the property’s FMV for purposes of determining loss. Likewise, under IRC Section 1015(b), the basis of property acquired by a transfer in trust (other than by gift, bequest or devise) is the same as it would be in the hands of the grantor increased in the amount of gain or decreased in the amount of loss recognized to the grantor on the transfer. Section 1015(b) has special rules that provide an increase in income tax basis for gift taxes paid, limited to a percentage based on appreciation % (at time of gift) to market value of the asset.

3. One set of proposals is set forth in Senate Bill S. 309 introduced by Bernie Sanders. S.309—116th Congress (2019-2020), dubbed “For the 99.8 Percent Act.” This article by Jonathan G. Blattmachr and Martin M. Shenkman summarizes Sanders’ proposal: https://blog.interactivelegal.com/2019/03/no-time-to-waste.html.

4. IRC 2035 does affect this statement, as gift taxes paid within three years of death don’t escape estate taxes.

5. Supra note 1.

6. Gifts of illiquid assets, such as partnership interests or closely held business stock, are usually valued at a discounted amount for both gift and estate tax purposes. The presence of either a gift or estate tax valuation discount can impact the gift-keep arithmetic. On a gift, the partner generally has a tax basis equal to the donor’s basis. If gift taxes are paid, they increase basis, but only up to the interest’s FMV. If a valuation discount is claimed, the FMV will be lower, and hence, the income tax basis adjustment for gift taxes paid will be lower. (Infra note 10 and Treasury Regulations Section 1.1015-5(a).) If the limited partnership (LP) (or closely held stock) comes through an estate and an estate tax valuation discount is claimed, the income tax basis the estate liquidated and property of the LP interest is distributed in-kind to the partners, the income tax basis of the property distributed will be reduced by the valuation discount claimed for estate tax purposes. See IRC Section 732(b).

7. Treas. Regs. Section 1.1015-5(c), (d).

8. See IRC Section 1245 and Publication 559, “Survivors, Executors and Administrators.” When certain types of depreciable property are sold, the seller must recognize, as ordinary income, the amount of accumulated depreciation associated with the sold property. However, when a real estate owner dies, a full basis step-up is possible; no ordinary income recapture occurs. If Section 1245 property is gifted and sold, the ordinary income tax would be paid.

9. Assets included in a parent’s estate for estate tax purposes obtain a new income tax basis under IRC Section 1014(b)(9) but not if assets acquired by the parent from a child by gift within one year of the parent’s death pass back to the child or the child’s spouse. Section 1014(e).

10. See IRC Section 2041(b)(1) and Section 2514(c) and Treas. Regs. Section 1.1014-2.

11. Treas. Regs. Section 20:2036-1(c) provides that when the grantor retains an interest in an annuity, the value of the property included in the grantor’s estate wil be the amount of property required to produce the annuity using the IRC Section 7520 rate in effect at the date of the grantor’s death. If, at the time of the grantor’s passing, interest rates have gone higher, a (potentially major) portion of the grantor retained annuity trust assets would escape estate tax. This is because if interest rates rise, less capital is required to produce the retained annuity that will be included in the grantor’s estate.

12. IRC Section 675(4)(C).

13. See IRC Section 2053(a)(4) and Treas. Regs. Section 20.2053–1(a). Families with large unrealized gains from assets that lack liquidity may be wise to consider the planning that occurred in Estate of Cecil Graegin v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 1988-477 (Sept. 28, 1988).

14. IRC Section 721(b) provides the general rule that gain is recognized when a transfer of appreciated stocks, securities or other property is made to a partnership that would be treated as an investment company under IRC Section 351 were the partnership a corporation. The determination whether a partnership will be treated as an investment company is made under Section 351(e)(1). A partnership will be treated as an investment company if, after the exchange, over 80% of the value of its assets are held for investment and are stock and securities (or interests in real estate investment trusts or in regulated investment companies). Treas. Regs. Section 1.351-1(c)(2) provides that the determination of whether a corporation is an investment company will ordinarily be made immediately after the transfer. To avoid gain, each partner must remain invested in the fund for at least seven years but may choose to remain an investor longer.